All Hail The Saint

Is Lord Benyon’s 14,000 acre estate an access-to-nature nirvana? That’s the claim of Patrick Galbraith’s new book, Uncommon Ground. Let's investigate.

Is Lord Benyon’s 14,000 acre estate an access-to-nature nirvana? That’s the claim of Patrick Galbraith’s new book Uncommon Ground, which seeks to rescue the great estate from criticism levelled by campaigners at Right to Roam.

The many inaccuracies and inadequacies of Patrick’s book are a subject for a future post. But I want to pick up on this one in detail, since he made it the crux of a piece in the Telegraph yesterday. ‘Stop Scapegoating Britain’s Landed Classes’ the headline pleads, with that particular tenor of maldristributed victimhood the right-wing press has perfected. Its central argument is that Lord Richard Benyon, former Conservative Minister and inheritor of the Englefield Estate, is not the villain Right to Roam makes him out to be. In fact, for Patrick, Benyon’s Englefield is a pioneer: his country seat a model for precisely the kind of countryside we should be aiming to create. Let’s get into the weeds.

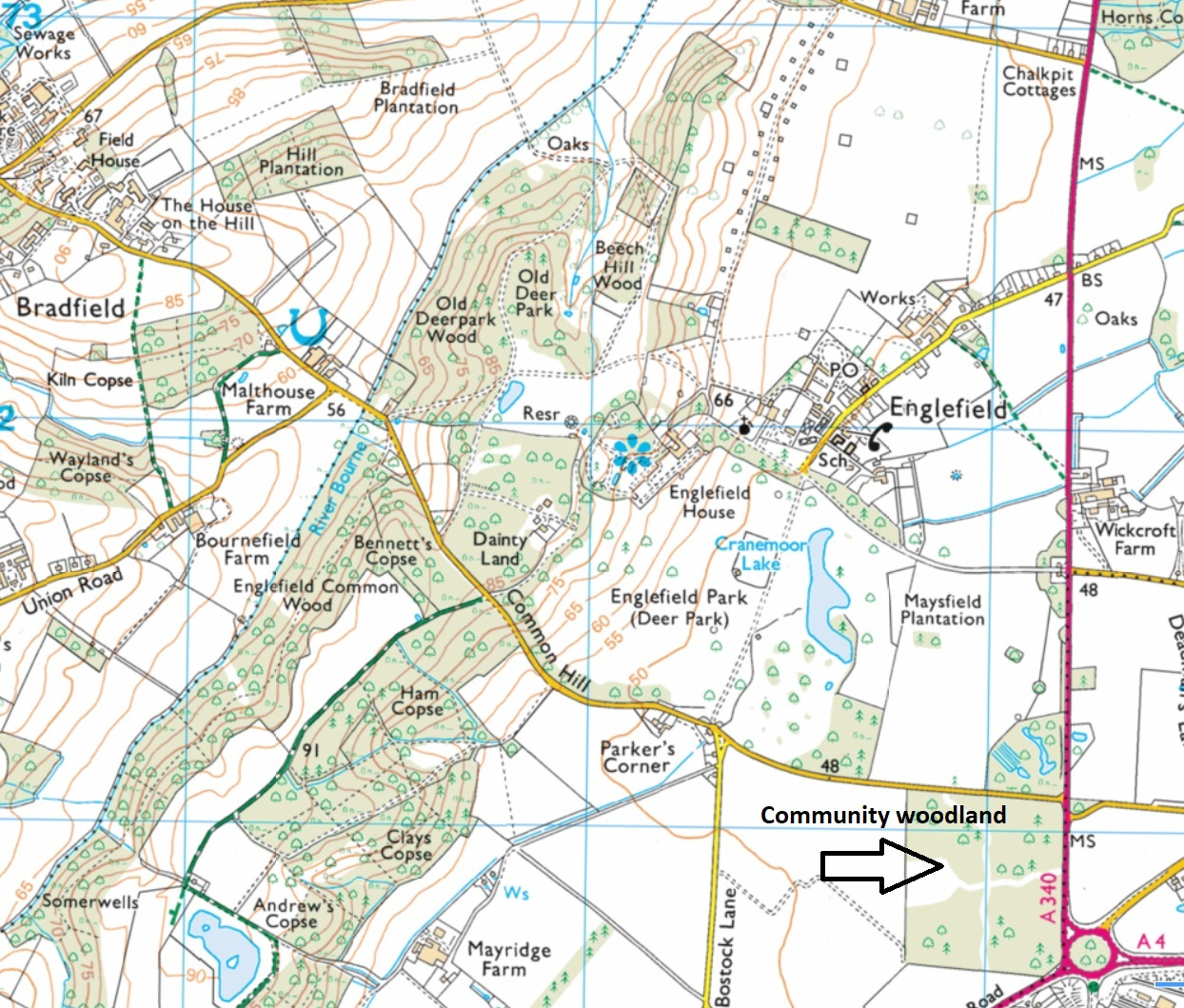

First, some context. The full landholdings of the Estate are huge and would probably take ten or so screengrabs to capture. But the heart of it, where the historic emparkment (walling off land to create a private park) took place, is below. Pretty much everything you can see here, excluding the villages themselves, is a part of it.

There are a handful of footpaths, which mostly connect one bit of road to another bit, or which take you along a service track skirting the edge of some nice-looking deciduous woodland you're not permitted to enter. There’s a ‘community wood’ in the bottom right. More on that shortly. Otherwise, when you compare it with the connectivity of the surrounding countryside, the Estate is a void.

That’s not untypical. Thousands of such estates polka-dot England’s countryside. Enclosure, emparkment, and aristocratic influence over the local administrative state ensured that many old paths and highways were magicked from the definitive map, either by sleight of hand or through outsized legal influence. The Rights of Way we see today are the scraps left from that process. I suspect they avoid those woods because they were (and in some cases, still are) coverts used for game; which also made them priority number one for exclusion.

You can see the impact. The way it fragments the landscape. Growing up in Bradfield, Bradfield Southend or the town of Theale, the walls of Englefield would serve as the hard exterior of your mental cartography. All reinforced by the royal blue estate signage, Keep Out notices and gamekeepers. Like other estates, there’s a weird, controlling feel to the place, which Patrick admits feeling too. Every cottage door must be painted the same colour. The old village was demolished for the deer park. The church is opened and closed by Richard’s mother. In short, it’s aphrodisia for a particular vision of Tory England.

Enter its patriarch: Lord Benyon, Patrick’s hero of the hour. The chapter on Englefield begins in that ‘community woodland’ highlighted on the map, maintained in the southeast corner of the Estate. He complained that we failed to mention its existence in the prologue of Wild Service, which opens with Englefield. And, fair enough – we did. It’s duly mentioned in the paperback.

From the map you might see why we didn’t catch it: it’s an odd patch of land hemmed in on two sides by the A340, a B-road, and some hedged-off fields. Unsurprisingly, it doesn’t seem too popular with the community it's named after. Patrick finds a handful of people mooching around who like it because they can drive there and no one else seems to know about it. Nick, who has lived in the area most of his life, had never heard of it. Because the access is all permissive and could be removed at any moment, it doesn’t appear as accessible on the OS map. That all limits its visibility – and viability. You’d need a car to get here. And other than a short, circular wander, where would you go anyway?

What about the main body of the estate? Patrick feigns surprise that the gateway to the drive is open when he arrives. In fact, the drive is one of two permissive paths within the main body of the estate, one which leads you up the asphalt for a bit to gawp at the Big House, before the other sends you along another vehicle track back to the busy A road. I’ve walked this route before and let’s just say it wasn’t an elevating experience. Still, Patrick finds a cheerful sounding Ghanaian man who’s just pleased to be there at all – he thinks it would be unlikely in Ghana. He wondered if he was allowed to walk on the actual green bits but felt the answer was probably that he couldn’t. He’s right. Keep off the grass.

The purpose of these permissive paths is a bit mysterious until you know why they’re actually there. They’re in fact the rather lame contributions to HMRC’s Tax Exempt Heritage Assets Scheme, which essentially allows big estates to get tax breaks in exchange for access to ‘heritage assets’ like parkland, monuments, works of art. You can see the submission on the HMRC website, which is otherwise broken, here. (More on the questionable nature of these arrangements here).

So an odd square of community woodland and permission to walk up a small stretch of the drive for tax purposes. Almost no rights of access at all. So where’s the rest? Since the trespass we held at Englefield in 2022, the Estate has added a section to its website promising that 1,700 of its 14,000 acres are available for public use. In one of the many episodes where Patrick seems to write a stick into his spokes, he wanders around asking where these fabled acres reside, since he clearly can’t find them. The old lady at the Garden Centre? No idea. The lady at the tea shop? Not sure. The receptionist of the Estate office? Doesn’t know either. Diligent readers will notice he never solves the mystery. Never mind, in the next scene we’re into an interview with the big man himself, who has Patrick truly entranced. Patrick leaves as a man on a mission: to restore Saint Benyon’s sullied reputation. A deeply cringe attempt to gatecrash the Bloomsbury publishing offices ensues.

The reason he doesn’t find them is because they’re about ten miles south of the main estate at an old bit of forestry near Silchester known as ‘Benyon’s Inclosure’. As the name suggests, this is all formerly common land, enclosed by the family in the 19th century and ultimately destined to be a commercial forestry plantation (and currently, a shale quarry). A few Rights of Way follow the forestry tracks, to which the estate has added - let’s be charitable - a good number of permissive paths. It’s not dedicated for open access, though, so along the lorryways you go.1 And it’s clearly not anywhere near 1,700 acres of access if you’re confined to such routes.

You can join Patrick in finding this mindblowing if you like. Personally, I’m less impressed. The main body of the estate, where the non-despoliated countryside exists, is, contra-Patrick’s protestations, almost entirely off limits. Everything given to access by the estate is the lowest hanging fruit. Reusing forestry tracks leftover from commercial exploitation in a forestry plantation might be better than nothing, sure. Hardly what I, and I expect Patrick too, would see as quality experience of the natural world. It would be no great difficulty to extend rights to more quality areas - even beyond the imparked area - while using justified conservation exclusions (which Patrick conveniently pretends we don’t believe in, since if he did, half the argument of half his book would fall apart) to keep people away from nesting lapwings.

There are worse landowners than Richard Benyon. There are worse politicians. Guy, who co-founded Right to Roam and who Patrick has an unhealthy obsession with, worked with Benyon constructively when he was a Minister to get support for good stuff like regenerating temperate rainforests. Really, he strikes me as your run-of-the-mill paternalist. All up for good works, school trips, and fundraisers so long as the order of things is preserved. I bet he always turns up to the village bake sale. It’s a well-practiced tradition of reputational offset which the gentry have long learned how to play.2 The approach to public access is the same: scraps to distract the dog from the dinner on the table. Dig through the archives and you’ll find striking 19th century accounts of the annual fete the-then Richard Benyon (they all inherit the paternal name) would host every year, when the plebs of Theale would be allowed in for the day (just the day) to resounding cheers of All Hail Lord Benyon! It’s a perfect distillation of our land conversation.

But Englefield doesn’t feature in Wild Service (the book with which Patrick takes such umbrage) because it’s an especial example of landed malevolence. It features precisely because it’s a bog standard example of an English aristocratic estate. It’s representative of the problem. It also features because of Benyon’s previous standing, as the Minister in charge of access to nature for all of England. What did he do with this power? It’s surely the first thing a serious reporter would ask.3 After all, Benyon was Minister when the Agnew Review was shelved – an inquiry established by the Treasury during lockdown to bring about “radical, joined up thinking” that would lead to a “quantum shift in how our society supports people to access and engage with the outdoors”. The review was supposed to be a response to the sacrifices of the pandemic and a solution to the intense access inequalities it exposed. But then, mysteriously, it vanished.

Benyon was also around when another Conservative access commitment, this one devised by Thérèse Coffey, that everyone should have access to green or blue space within fifteen minutes of where they live. Yet when we FoI’d DEFRA to find out what progress had been made to advance the policy, we discovered a decision had been made to not make the commitment legally binding – which is the government's polite way of saying they have absolutely no intention of actually making it happen. The Secretary of State, George Eustice, was the first to query the binding target. But to whom was the relevant decision memo addressed to? Richard Benyon.

Government is complicated, and perhaps Benyon has good answers to these questions. But Patrick never asks them. The whole interview is an embarrassing example of how not to probe a senior politician well practiced at saying all the right things. Instead Patrick gives a gushing portrait of beneficence; all school visits and worries about young families in Mortimer. It’s true that Benyon comes out with some pretty cosmic stuff for a man within the landed system. He apparently poo-poo’d the claims made by the Country Land and Business Association that opening up the countryside to more footfall would be a “disaster” in the run up to the Countryside and Rights of Way Act. Though Patrick never explains why we shouldn’t still ignore such claims, like the ones he continually makes throughout his book. Suggestions of apocalypse have preceded every extension of access rights in Britain. Funnily enough, the apocalypse never comes to pass.

During the interview Benyon states that when Right to Roam turned for the trespass at Englefield we were “infuriated” by his order to his staff to be non-confrontational, “because they [Right to Roam] want confrontation.” He couldn’t be more wrong. In fact, as Patrick knows from attending our workshops, one of the core campaign principles is non-confrontation. To be polite. To seek, where possible, areas of common ground. The autumn before, a handful of us had gone for a reconnaissance around the estate and were confronted by Benyon’s gamekeepers. It was the usual macho bluster at first. But we remained as we were, sitting calmly beneath a venerable Oak tree. When it was clear we weren’t too flustered, the dynamic began to shift and we got into a good conversation covering all sorts of rural issues. I reckon we chatted for about 40 or so minutes in all. We shook hands and headed off in opposite directions; understanding each other a little better, while looking at the world a different way.

Some of this provision appears to have been a part-trade for an unpopular quarrying operation the estate recently undertook in the area.

And of course, there has always been a wing of the media whose role is to help them play it. It’s instructive to read Patrick’s dewy-eyed interview alongside similar reportage of such estates in the 19th century. Everything changes, everything stays the same.

It is clear from Uncommon Ground that a serious journalist Patrick is not. His approach is often to populate his writing with gossip from casual conversations in which people are not on the record, before presumably reporting it from memory later. It’s awful journalistic practice, both for ethics and accuracy. And impressively self-defeating for an early career writer in a small field where everybody knows everybody. Fool me once…